Ever wondered why the Catholic Church celebrates the Sacred Heart of Jesus in June? Here’s a brief article to explain why…

Why is June dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus? (aleteia.org)

Ever wondered why the Catholic Church celebrates the Sacred Heart of Jesus in June? Here’s a brief article to explain why…

Why is June dedicated to the Sacred Heart of Jesus? (aleteia.org)

New term, new priest.

The Catholic Chaplaincy welcomes Fr Michael to the team.

Here is his bio:

Fr Michael is the Catholic Chaplain at the University of Lancaster and Episcopal Vicar for Education and Formation in the Diocese of Lancaster.

He is the parish priest of St. Mary’s Hornby and St. Joseph’s Kirkby Lonsdale.

After completing a history degree at the University of Nottingham he taught in Dover prior to studying for the priesthood at the Venerable English College in Rome, where he specialised in Dogmatic Theology.

Fr Michael been a priest for many years and served in parishes across the Diocese of Lancaster as well as in the field of education.

Mass will resume at the Chaplaincy Centre on Sunday 27 September at the slightly different time of 6pm. The present Covid pandemic has restricted our chapel capacity to 36, and so there is the possibility that people may not be able to fit into the chapel for Mass. For this reason, following Welcome Week, there will be a choice of Sunday Masses on campus, one at 4.30pm and one at 6pm. If we have reached the limit within the chapel, please tune into the ‘Lancaster University Catholic Chaplaincy Centre’ Facebook page and you can join in the Mass online, and then come and receive Holy Communion at the end of Mass. In between each of the Masses, the church will be cleaned and sanitised to ensure a safe environment for students and staff. Unfortunately after Mass we are no longer able to offer refreshments and cake; however, we will be handing out Thermal Mugs and you can fill these up with tea beforehand and bring it with you and enjoy it (in a socially-distant way) after the Mass with others. Finally, please be assured that you can visit the Chapel during the rest of the week: the doors will be open and you can come in for quiet prayer. You are asked, however, to sanitise your seat after you have sat on it with a Dettol wipe.

If you are living in town, Mass will be available in the surrounding parishes, subject to any restrictions brought about by the Coronavirus:

St Peter’s Cathedral, Balmoral Rd, Lancaster LA1 3BT. Saturday Vigil 6.30pm, Sunday morning 10.30am, Sunday evening 6.30pm. Weekdays at 12.15pm.

St Bernadette’s, 120 Bowerham Rd, Lancaster LA1 4HT. Saturday Vigil 6.30pm, Sunday morning 11am

St Joseph’s, Slyne Road, Lancaster LA1 2HU. Saturday Vigil 6.30pm, Sunday morning 10.00am.

Whilst Fr Philip will be around on campus, you can always contact him through St Joseph’s parish: 01524 32493, or by email.

Covid regulations: As per the instructions from the Bishop, those who can wear facemasks are asked to wear them in the chapel. There is no congregational singing. The Sign of Peace is temporarily suspended to reduce any potential cause of transmission of coronavirus.

Please continue to practise good hand-washing hygiene, and remember these measures are not intended to cause panic, but to introduce sensible precautions to help everyone stay healthy. For this reason, the holy water stoup has also been removed, and people are asked to receive Holy Communion by hand. If you are feeling in any way unwell, please do not come to church and please self-isolate and follow relevant medical advice.

Should Masses be cancelled in the near future, please keep in touch with livestreaming of Masses and services through the Catholic Chaplaincy Facebook page and make use of the wonderful resources that we now have at hand on the internet: in particular the Readings for Mass can be found on the universalis website, and you can order Magnificat, a publication which includes daily prayers and the Mass readings of the day, from the Catholic Herald. Please continue to pray the Rosary and read the Scriptures each day for an end to this virus and for peace in our world.

2019 marks the Golden Jubilee of the Chaplaincy Centre, 50 years of wonderful things. As part of the celebrations which brought together past and present chaplains from the past fifty years together with students and staff, Marion McClintock presenting an inspiring account of the Centre’s history which is reproduced with her permission here.

Queen Elizabeth II with Fr John Turner, first Catholic chaplain to the University of Lancaster, on 17 October 1969

University of Lancaster Chaplaincy Centre, 1969 to 2019:

Honoured guests, ladies and gentlemen, thank you for your kind invitation to speak in commemoration of the Centre’s 50th anniversary. I am honoured to do so and to reflect on the special place the Centre has in the life of the University. I, and no doubt others present here this afternoon, were at the dedication of the Centre fifty years ago, and I wonder whether any of us had the temerity to assume we would be present at such an occasion as today’s celebration?

The service of dedication took place in the late afternoon of Friday 2 May 1969. The procession that entered the central concourse included representatives of: Methodist, Baptist, Congregational, Presbyterian, Church of England, and Roman Catholic churches, together with the chaplain and counsellor to Jewish students. The acts of dedication were performed as follows: the dedication of the Centre overall; the Jewish Rooms; the Anglican and Free Church Chapel, and the Roman Catholic Chapel. The seven chaplains were commissioned, and on behalf of all of them, Father Matthew Shaw made this commitment:

We pray that we may truly be thy ministers, serving the members of this community in their thinking, their hopes and fears, successes and failures, aspirations and disappointments, popularity and loneliness, faith and unbelief. Grant to us, and our successors, a constant love and growing understanding of staff and students alike, minds alert to new ideas, hearts sensitive to varied personalities and relationships.

Simple and strong words, but what decisions and choices lay behind that dedication? Why have a chaplaincy centre at Lancaster? One of the fascinating features of Lancaster, despite all its early documentation, is how much information remains to be uncovered. Perhaps people here this afternoon will be able to fill some of the gaps I shall reveal.

Queen Elizabeth II shaking hands with Bishop Brian Foley

To consider that question, let’s go back five years earlier, to a university that has Quaker grey – a reference to our founding vice-chancellor - as one of its two colours. In its founding week, the university community went first to church. Two services were held on Friday 9 October 1964. The first was at Lancaster Priory, where the Archbishop of York preached on the theme of repentance in the presence of HRH Princess Alexandra, incoming Chancellor to the new university, Charles Carter as vice-chancellor, and Hugh Pollard as the principal of S. Martin’s College, the Church of England teacher training college at Bowerham dedicated by the Archbishop later in the day.

Also on 9 October an academic mass was held at St Peter’s Cathedral. That invites us to go back a further four centuries, to a Lancashire where gentry families and local communities ignored the Reformation and held onto the pre-Reformation Catholic faith. When the Roman Catholic Relief Act was passed in 1791, a Catholic mission church was shortly afterwards founded in Dalton Square. In 1857 the foundation stone was laid for a new and much larger parish church, dedicated to St Peter, that became the Cathedral for the new Diocese of Lancaster in 1924. In the 1960s the Roman Catholic church in north Lancashire thus had the standing and the resources to take new initiatives. The appointment of Bishop Brian Charles Foley in 1962 is also I think significant to this story, as well as the energy and wholehearted commitment of the first Roman Catholic chaplain, John Turner.

We should therefore not be surprised - although I admit I still am to a degree - that the first the site development architect seems to have heard of a proposed dedicated chaplaincy building was a letter of 22 June 1964 from Gerald Cassidy, at a new firm of Preston architects, Cassidy and Ashton. Instructed by Bishop Foley, the request was for a meeting about the location of a building “purely for the purposes of Catholics attending the university”, including a resident chaplain and some public spaces, that might be at the north-west corner of Alexandra Square. Stephen Jeffreys, founding University Secretary, responded with a clear understanding that space on the site for a religious centre should also provide for other denominations, and that decision led to planning discussions over the next two years that evolved into what we see today. Not only were Christian denominations to be involved, as by the end of the year, the Jews had also expressed a wish to be associated with the new centre, using the Hillel Foundation as a source of funding.

By May 1965 a small group, consisting of the Vice-Chancellor, the Bishop of Blackburn, Bishop Foley, and the Revd Maland of the Methodist Church had come up with a statement of need. This involved two important compromises: that the Roman Catholics would have their own chapel, and that a second chapel would be shared between the Anglicans and other Protestant churches. The upper floor would be used for resident chaplains, guest space and smaller meeting rooms. A funding target of £145,000 was set and design work began in earnest.

Chaplains past and present, and friends of the Chaplaincy Centre

I had the pleasure in March 1973 of meeting Gerald Cassidy and he spoke eloquently of the aesthetics of the building: three tulip petals, each one perfect, but stronger when united. In a written note to me he said:

As soon as the brief began to clarify, it was felt that, anxious though the churches were to preserve individuality of worship, there must be no thought of two quite distinct chapels linked (and separated) by accommodation for communal activities. The individual elements of two chapels and other accommodation were seen to be of equal importance, but subservient to the whole theme, and the process of design forced the conclusion that by far the most important feature was the link which quite literally held the pieces together.

The shape follows naturally from this philosophy. While the identity of each element is preserved, each develops into and is swept upwards towards a tripartite spire surmounting and giving majesty to the central link area and enabling it to dominate the whole. . . . The underlying feeling throughout is unity without loss of identity, with full scope, as is proper in a university, for liberal experiment both in liturgy and in worldly action.

The resulting building seems to me to be a triumph. Externally located on its prominent site, it gives visual variety and vigour from the approach road with the three upswept spires, eminently contemporary in their steel framing and white plastic cladding, that sit above the three drums clad in the same Stamford buff brick as their near neighbours. The rhythms of fenestration and entrances are beautifully controlled, with the strong verticals of door framings and narrow and wider widow openings complementing the three drums. Internally the chapels each have their own distinctive character while being respectful of each other. The silence, stillness and uncluttered central concourse give repose and welcome, and direct the incomer’s gaze upwards and outwards, while the third drum has a different function as a place of sound and movement. Meanwhile, the upper floor has a pleasing domesticity about it that is safe and reassuring. The building has an enduring appeal that does not date and is timeless, because the values underpinning its form are also timeless.

Bishop Paul Swarbrick celebrating the Mass of the Holy Spirit this year, inaugurating the new academic year, and thanking the Lord for the past 50 years. Bishop Paul is flanked by some of the previous Catholic chaplains together with Fr Philip Conner, to the bishop’s right on this photo.

There was however the little matter of the three crosses. At a fairly late stage the Jewish students complained about having a Christian cross above all three of the spires over accommodation that included Jewish sacred space. The discussion became quite heated and, after the completion of the building and before its dedication, the horizontal arms of the tallest cross were cut off, leaving a simple spike. The story that Ninian Smart, founding professor of religious studies, personally climbed up with a bolt cutter is, I am afraid, an urban myth. It was however the case that the Bishop of Blackburn expostulated for a while about fitting the spike with a fish symbol, but in vain.

The other often-quoted story is that H.M. the Queen undertook a second dedication of the Centre later in 1969. Alas, the facts tell us otherwise. She went to each of the new universities in turn, and Lancaster’s visit on 17 October 1969 was heralded as a visit to North Lancashire, starting with the Castle and LRGS, and concluding with Myerscough College. She spent 90 minutes at Bailrigg, her car arriving at 10.45 and leaving promptly at 11.45 a.m. During that time she met officers at University House, walked through Alexandra Square, and went by car to County College where she unveiled a plaque and had coffee with students. She then walked through the Great Hall complex to the Chaplaincy Centre, where nineteen people were lined up to meet her, and was given a conducted tour that I am assured included the Jewish rooms. She also, said John Turner, had a brief opportunity to kick off her shoes and rest her feet. That is not a schedule that allows for the solemnity of dedication.

Therese Monaghan, current CathSoc President, carving up the Chaplaincy Centre!

From the day of dedication onwards, staff and students immediately assimilated the new centre into their routines, using the centre in diverse ways. The beginning of academic year services took place here from 1969 onwards, and debates, tea parties, exhibitions, lectures and seminars competed for the space available. The service of Songs of Praise was broadcast in 1971, and on the tenth anniversary Bishop Trevor Huddleston came to preach. Almost every liturgical practice that could be thought about has taken place at least once. There was a wide range of denominations and faiths represented: in the mid-90s, for example, Anglican, Roman Catholic, Methodist, Baptist, United Reformed, Unitarian, Christian Brethren, Society of Friends, and Jewish and Buddhist.

Individual students quickly recognised the Centre as a place where the welcome was consistent and real, and particularly at examination periods when stress levels rise. Staff across the university were involved by means of weekly newsletters, Angle and then CentrePoint, and for a time staff lunches and seminars were organised. At times of institutional difficulties and strained relaionships, the Centre was a neutral place where people could meet informally in a way that was not possible at any other place in the university.

A wonderful spread of food for all the guests at the celebrations

Funerals and memorial services were held, as well as weddings and musical performances. For a time a highly successful café, George’s, did a roaring trade, but tastes and circumstances are constantly on the move and it became unsustainable. At least two chaplains became principals of the university’s colleges, and a management committee chaired by a senior member of the university has ensured close liaison between chaplaincy and university.

Structurally the building has stood up well, and the university has been supportive in its willingness to keep it in good condition. The most unhappy event was a small but nevertheless damaging fire in the Roman Catholic chapel, which served as a reminder of the fragility of fittings in a building such as this. Interestingly, there were discussions in the early 90s about whether the university should have a mosque. This would have been quite a large building, at the position on the perimeter road where the Health Centre now stands. For a variety of reasons, including finance, this did not proceed, and successive forms of alternative provision have been made for the Muslim faiths.

I asked earlier, why have a chaplaincy centre at Lancaster? Of the Shakespearean Seven universities of the early 1960s, Lancaster was the only one to initiate such a centre. The days when prince bishops endowed universities are long gone and modern universities regard themselves as secular institutions that work through business models. Budgets and annual accounts, national and international league tables, student recruitment and graduate employment, resource allocation and strategic direction, quality assurance and research funding, these make up the hard realities of higher education in the 21st century. Why should Lancaster be different and, if I may be presumptuous, what might its role be for the future?

A full house for Marion McClintock’s talk

Inevitably I speak from within the tradition that I personally know best; the Anglican church. However, I also speak within an institution that had Ninian Smart as the founding professor of our Department of Religious Studies. In his inaugural lecture of February 1968 he listed the distillation of the originating syllabus: the study of modern religious and atheistic thought in the West, comparative and descriptive studies of religion, including the history of Indian religions, sociology of religion and the phenomenology of religion, and biblical studies, chiefly the New Testament. What an interesting list, and note the position occupied by biblical studies! Although the discussion about whether to have his department post-dated the decision to have a Chaplaincy Centre, and the two should not be confused, nevertheless Lancaster has consistently been a place where fearless examination and debate of controversial issues, including religion, has flourished. It has been suitable place for a department that has helped to define world wide how religions can be studied.

A delicious cake was enjoyed by all!

I see university chaplaincies as having a particularly privileged position. The parishes within the Church of England have churches that typically care for members of a particular community; know their people, (usually) have agreed liturgical positions, and are at the historic core of village or town. The 42 cathedrals, on the other hand, span England and in the words of Martyn Percy (2017) [the recently re-instated dean of Christ Church, Oxford] are typically low threshold. By this is meant anyone can come, without any need or pressure to join a rota, a group or a class, and this is combined with high reward; superb music, preaching of high calibre, and an elegant and well-delivered liturgy. Chaplaincies are anomalous in a good way. They have a free-flowing and constantly changing constituency, like cathedrals; they care for individuals like parishes; they make their own history through their involvement with a particular academic institution and its culture and values. Lancaster has benefitted from this freedom to choose and change and evolve, and has done so across Christian denominations and world religions.

Lancaster is also fortunate in its location. Universities in city centres, with buildings widely separated and adapted from other uses do not make for a sense of shared destiny. Here at Bailrigg the founders of the university were able to work from pasture land to form the campus that we have today. Their early choices in particular were of critical importance in establishing Lancaster’s institutional personality. Those choices included a chaplaincy centre that is distinctive, prominent and unmistakeable, and which conveys a sense of welcome and openness. I well remember coming here the day after Storm Desmond had extinguished electricity across Lancaster, and the university had ended the term a week early. In the twilight of a December afternoon, hundreds of students clustered quietly in this area of the university, waiting for the coaches that would take them to their respective destinations. I was struck that by some quirk of infrastructure, the lights of this building were still on, and gave illumination to what would otherwise have been a desolate scene. It seemed symbolic.

So, to sum up, I suggest that the reasons why we have a chaplaincy, and a chaplaincy centre are as follows. First: historical, about the region in which we are situated; secondly because we are an institution where truth lies open to all, whatever their background or faith - or absence of it; thirdly because we have the gift of this building as a beacon on the hill; and fourthly, because of the excellence of the chaplains and counsellors over fifty years and into the present, supported by the university and valued by our students.

David Martin is another theologian who has been involved with Lancaster, and I hope he would accept that words of his from 1998 that I now paraphrase have a wider resonance that are relevant to this chaplaincy. He refers to a repository of all-embracing meanings, pointing beyond the immediate to the ultimate, an institution that deals in tears and concerns itself with the breaking points of human existence, an entity that provides frames of reference and signs to live by. Those words sum up for me an important message for those who draw on this centre and care for it.

So, many congratulations on your first half century. May the second fifty years of this outstanding chaplaincy contribute as strongly and consistently to the life and work of the university as the first fifty years have triumphantly done.

Marion in full flow!

A group of students joined 40,000 young people from around the world at the beautiful shrine of Medjugorje this Summer. Here are a few photos of this fantastic international festival of prayer and fellowship.

Arrival at Santiago de Compostella

A group of 16 students completed the Walking Pilgrimage, following ancient routes, to Santiago de Compostella where the apostle, St James, is buried. Setting off from Vigo, we set off each day, not knowing where we were going to stay, what we were going to eat, who we were going to meet, how we would get along, and what would befall us.

Bathing our feet in the thermal springs at Caldas des Reyes

Battling the grit in the boot, the rub of the blister, the heat of the day, the snoring of the night, the laughs and the tears, the weariness and the elation, we all arrived together, rejoicing that we had come to our journey’s end, somehow changed by the whole experience.

Mass on the way, at Padron

Sunrise

At Pontevedra

Here, our roving reporting, Lisa Vallente-Osborne writes up the experience of a lifetime: ‘When people told me the Camino was life changing, I have to say I didn’t believe them. It was a long walk; how could that really change someone?

The week before we set off, the crisis happened began. I realised I was terrified. What if I couldn’t do it? What if I couldn’t keep up? What if mentally it wasn’t for me? What if I didn’t like the person I was to become? So I prayed... and this voice responded.. ‘what’s wrong child? It’s just a long walk with me, like I did all the time with the disciples’! I will be there, you won’t be doing this alone’.

The Camino took us through the extremes. Beautiful valleys, hideous industrial estates, peaceful countryside and busy towns. The contrast on the senses was unique. As your ears settled to one sound, they struggled to adjust to another. The smells! Once your sense became accustomed to the country, you could smell you were coming into a built up area because of the smell of decay, drains, bins and lots of people.

The sleeping arrangements are quite unique and character forming! Sharing rooms in hostels, often with 40 or more people of a night. It was freeing walking with your world in your backpack, not knowing where your next bed was going to be, or who would sleep beside you! Yet, there was a sense of awe at night as you listened to the sounds of breaths changing (and the odd bit of snoring) because you knew that every single person here tonight, as was last night and will be tomorrow night- a pilgrim; walking the way of the Lord. We are that one body that St Paul talks about, moving forward in the way of love.

The Camino mounds you. Every step you take impacts the last, and your joints and feet ache. You have to find a way and a focus, keeping one foot in front of the other, finding strength from yourself, others and prayer. It’s in this pain and at times despair, that your mind focuses on the intention. Why walk this way? For personal gain? Or something far more? Like a flash mine came through, my walk was for my Godson, who at the tender age of 10years has Duchennes Muscular Dystrophy. He has experienced more pain that I could ever imagine. My pain was for the duration of my walk, his for the the rest of his short life, as each muscle wastes away till eventually his heart and lungs simply won’t work. It’s for those that can’t do this, that we walk. Giving ourselves entirely over in a physical prayer and offering, uniting body, soul and spirit.

The Camino gives you an new appreciation for your God given physical body. As each kilometre passes, you become ever increasingly grateful, that this physical being has and is still carrying you through this walk and life. So many times we are stuck in our heads, too busy with life, we often forget we have bodies. They are an annoyance, something to cover up or abuse with drugs, food, or starve; yet He made us in His image. The media is very good at making us dislike our physical form; lumps and bumps not quite in the right place; but the Camino forces your to celebrate it, warts and all. Once you realise that your body is a God given gift, you look at others that you pass on the walk in a while new way; giving increasing respect and compassion to that 70 yr old couple, the woman in her 90’s that you keep overtaking, the young couple with the baby in a buggy. We are all images of God, and what a diverse and beautiful image we are!

By the time you reach the square at Santiago de Compostela you’re empty. The last day’s uphill stretch is relentless, and then the last part through the town is difficult. Your tired, sore, hot and trying to dodge people going around their everyday life. It’s noisy, overstimulating and smelly. You arrive in that square with mixed emotions and the shedding of tears is common. You’re elated that you got this far, but saddened as this journey ends. But to see the Cathedral of Santiago it all its glory is magnificent!

Walking into the Cathedral, it like a long cool and much needed embrace. We joined the pilgrims queue to hug St James the Apostle, to hand over our Camino intentions.

Whilst hugging a cold lump of gold may look and seem stupid, there is a finality in the motion. With your arms around the statue, St James reminds you of the thousand of pilgrims who have done this, who have walked this way. Billions of intentions lay on these shoulders, humanity’s plea for something better for someone suffering. It’s a humbling and stark reminder that we are not the same people who set out in this road. Every passing hour, every passing kilometre has a changed us, made us look at life in a new way, made us look at others in a new way. This body has ‘emptied’, and in the process has made space for the new wine, the divine wine. It’s is this losing of the ‘self’ that you stop fighting, and let God in.

The pilgrims Mass is a celebration. All walks of life, all nations together, to celebrate in worship and prayer. If you’re really lucky you get to see the ‘Botufumeiro’- the thurible the size of a mini flying across the nave of the church bellowing our it’s sweet aroma! Whilst in the past it had been used to ‘fumigate’ the church due to the smell of well travelled pilgrims, now it’s just a showpiece. But if you look away for a moment from it’s display and look around you, what you see are the faces of God’s children shining, gleefully smiling in defenceless joy.

So, has walking the Camino has changed my life? Yes! (Said with certainly). In the process, I didn’t find ‘me’ but God certainly did! The challenge now is to walk the rest of my life’s Camino, in the same spirit!

Buen Camino!

Looking over the last academic year, it is impossible to capture how many wonderful things happened, how many blessings, how many beautiful people and friendships, and how good God has been to us all. But hopefully, in a few pictures, some of the memories of 2017-18 will be stirred up again, as we reflect upon the good old days!

Trip to Liverpool, in search of the Beatles

The Breakfast Club, every Thursday

Christmas celebrations

Retreat at Ampleforth Abbey

Piano concerts in support of local charities

Bosco photoshoot

Trip to the Lake District

Time down at the beach

Post exam de-stress

Commitment

Pilgrimage to the Eternal City to see Pope Francis

Outing to Kirkby Lonsdale

Fun on the farm

Graduation. Congratulations to all those who graduated this year!

University is a place where people explore the depths of life, engage their minds and hearts, encounter their faith in a new way, and meet new friends who share and support them in the faith. It is always a great encouragement when young people gather the courage to step out, as it were, onto the waters, just as Peter did. This Easter two students were received into the Church and three others received the Sacrament of Confirmation. We were delighted that our new Bishop, Rt Revd Paul Swarbrick, was able to be with us to celebrate this great occasion.

Here, Rani, who is from Indonesia, shares what the day meant to her.

“Reflection on being Baptized (22 May 2018) It has been almost two weeks now since my baptism. Within the first week, people congratulated me – be it in person or via Facebook and Instagram. Even those who I did not usually speak to, drop a message to congratulate me. Then came the questions:” why did you get baptized?”, “did you convert?” and reactions like “It’s brave of you to get baptized”. Regardless, what awes me the most is that what I thought to be a personal faith affirmation sparks various discussions regarding faith. A Hindu friend asked about what being baptized means; discussion with Muslim friend on faith journey; some Eastern Orthodox friends talked about how they were already being baptized since baby and become a Christian by default, not having the opportunity to experience what I just had. Yesterday, I had the privilege to share with a born-Buddhist friend who has been thinking to get Baptized for some time. I did not – in my wildest imagination – imagine of things like this happening because of someone getting baptized. Who would have thought that what you experienced can causes ripples in other people? Being baptized, and receiving the Eucharist has been a longing.

“It all started with an innocent desire: to be able to receive the Holy Communion. During Friday Masses when I was in primary school, I used to look at my friends who were lining up to receive the Communion in jealousy. Then there was the matter of continuing to a Catholic junior high, but had problem because although my family register stated me as Catholic but I could not produce Baptist certificate when asked. This event marked the start of my faith journey. I have been exposed to both Catholic and Christian teachings in the past decade, both through school and life events. I found myself turning toward God the most after tremendous griefs at life to find healing and encouragement, and these same times brought awareness and questions to what I really believe in. As I attended sermons, Bible study groups, interacting with both Catholic and Christian friends, there were some points when the longings intensified. Yet something is still missing. Something does not yet click. It was not until Sukriti who invited me to Christmas Eve Mass and attending several Masses in the New Year that finally it clicked. The realization that Catholic Church is universal, of its unchanging nature and its love toward even people from non-Christian beliefs brought inner peace. After praying and some self-affirmation, I decided to email Fr Philip on 24 January 2018. I did not know that when he read it the next day, it was the feast of the Conversion of St Paul the Apostle until he told me. And the rest is history.

“To sum it up, I would say the whole experience is both beautiful and wonderful. The few days before the big day, I got the impression of the whole waiting thing like a bride-to-be counting for the wedding day; excited and nervous at the same time. Afterwards, you realize that God works wonders in unimaginable ways which He will do even more through us in this point onward”.

Last year as the first snows fell upon the country, a group of students from the Catholic Chaplaincy ventured across the Pennines to Yorkshire to the old Benedictine Abbey at Ampleforth. The weekend away was a time of deepening friendship, time for reflection with some excellent talks, profound times of prayer with the monastic community, great food, and snowball fights.

Before...

During...

After!

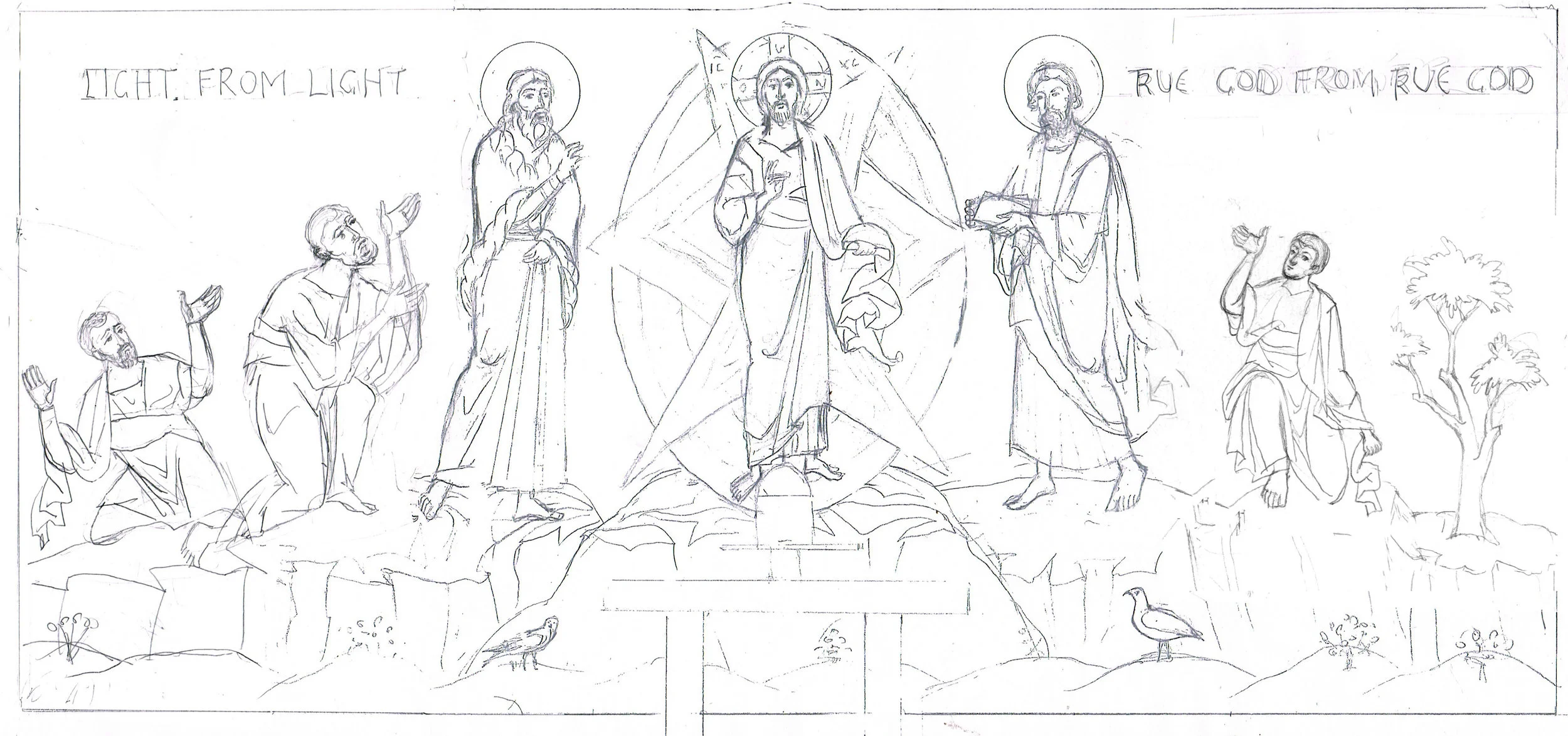

The Fresco of the Transfiguration in the Catholic Chapel is now complete. The internationally-acclaimed artist and iconographer, Aidan Hart, together with his team of Fran Whiteside and Martin Earle, completed the sacred image. There is timelapse footage of the whole project, two and a half weeks work in two minutes! Already the project - which is a significant contribution to the Christian patrimony of North-West England - is being recognized and has been reported in international journals.

After all the drama of the project's development, now is a good opportunity to reflect once again upon the story of the Transfiguration, why the subject was chosen for the University setting, and what the image says to us today...

“Jesus took with him Peter, James and John the brother of James, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. There he was transfigured before them. His face shone like the sun, and his clothes became as white as the light. Just then there appeared before them Moses and Elijah, talking with Jesus. Peter said to Jesus, “Lord, it is good for us to be here. If you wish, I will put up three shelters—one for you, one for Moses and one for Elijah.” While he was still speaking, a bright cloud covered them, and a voice from the cloud said, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased. Listen to him!” When the disciples heard this, they fell facedown to the ground, terrified. But Jesus came and touched them. “Get up,” he said. “Don’t be afraid.” When they looked up, they saw no one except Jesus”. Matthew 17:1-8.

The experience of Christ’s Transfiguration on the mountain is one of the most mysterious events recounted in the Gospel, revealing to us the fullness of who Christ is. To outsiders Christ must have been considered just another baby born in Bethlehem, another boy growing up in Nazareth, another carpenter working in Galilee. There was nothing to catch the eye, nothing to dazzle. But conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit within the womb of Mary, the Scriptures speak of how Christ, though in the form of God did not cling to his divinity but humbled himself and took on our human flesh. Whilst on earth, perhaps the greatest miracle of all, was that Christ’s glory remained veiled. But in this moment of the Transfiguration, the disciples – Peter, James and John – behold the glory of Christ. They are to understand that the man who stood before them was truly also the Son of God.

It is important to remember that this event took place within the context of prayer, and it is in prayer that Christ’s true identity is revealed to us. The Transfiguration is most apt for a university setting:

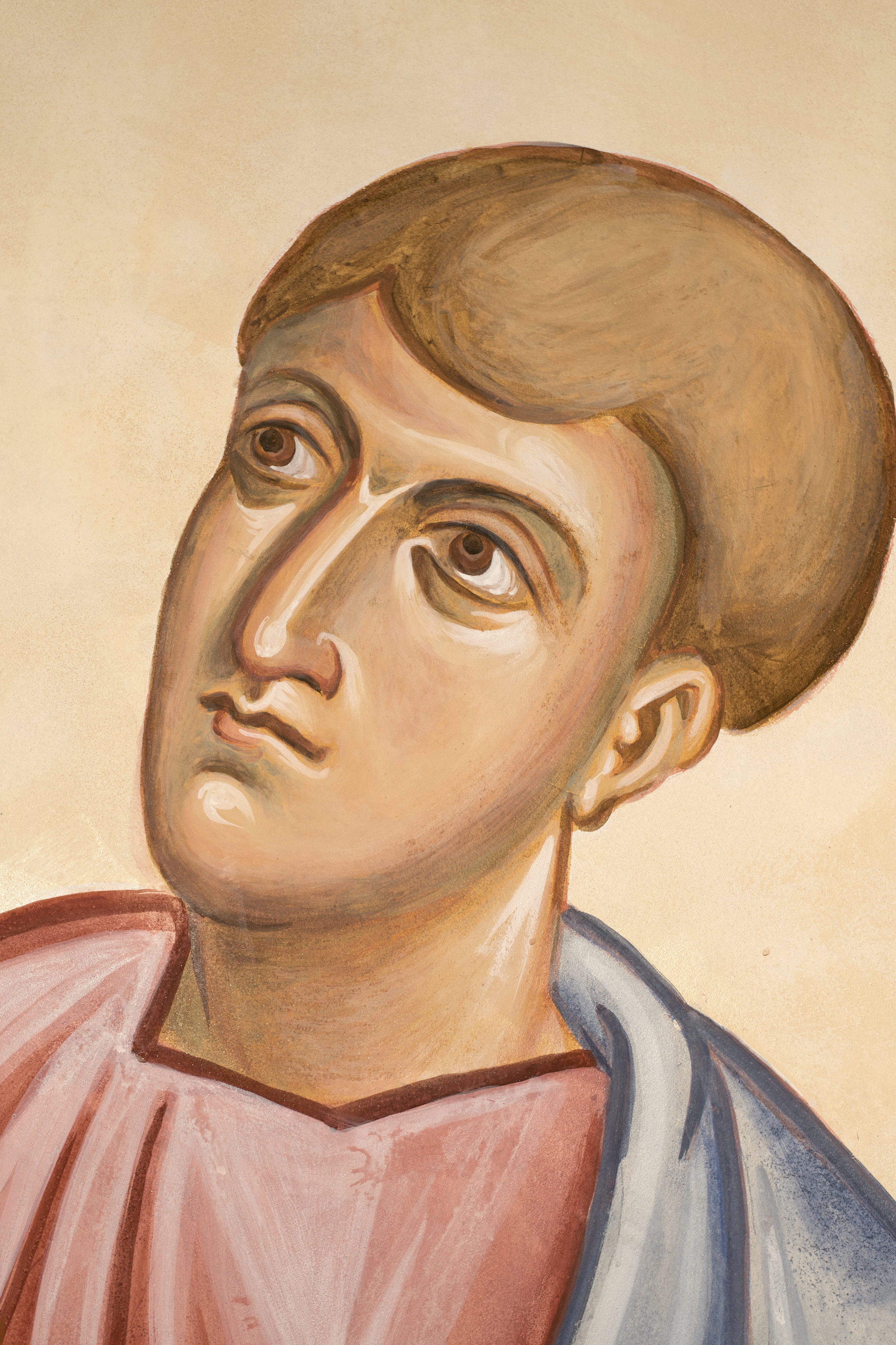

· First of all, there is the sense that Christ as the Teacher is revealing the truth to his Disciples, now as then (discipuli in Latin means students). One of the disciples, John, is without a beard for he was traditionally the youngest of the apostles, perhaps little more than 16 or 17 years of age, reminding us that the Lord calls us to His side from our youth.

The youthful apostle, John.

· The mountain too is an ancient image of ascent, the movement up and outwards from oneself, the leaving behind of what is familiar and the discovery of new views. In Christ, there is no contradiction between faith and reason, between the created world and the uncreated world, for in Him – the Logos – all creation has its being. All education should lead us out of the shadows of ourselves into the light of Reason.

· The Transfiguration says everything about who Christ is. As all the figures in the image look upon Jesus, Jesus looks upon us, inviting us to draw near to him, and discovering the truth of our identity in Him. Only in beholding Him will we ever discover who we are and what we are made for, that we too are called to be clothed in light, and we too are God’s beloved children, His sons and daughters, in whom He is well pleased.

· Finally, the role of art. ‘Beauty’, writes Pope Benedict XVI, ‘whether that of the natural universe or that expressed in art, precisely because it opens up and broadens the horizons of human awareness, pointing us beyond ourselves, bringing us face to face with the abyss of Infinity, can become a path towards the transcendent, towards the ultimate Mystery, towards God’.

Aidan Hart presenting the progress to a visiting group of icon writers from the NW of England.

Who’s Who?

Christ, in the early stages of his Transfiguration! The first coats of paint applied.

Christ – radiant in light, raising his hand in a sign of blessing. Notice the gesture of his hand of blessing: the two fingers together represent his divine and human nature whilst the three fingers together point to the unity of the Godhead, Father, Son and Holy Spirit. In his other hand, Jesus holds the scroll of judgement, which, for the time being remains rolled up, affording us time to respond to his call. The mandorla (which represents the radiance of the luminous cloud, signifying the majesty and glory of Christ) is blue, a colour which in iconography denotes divinity. Christ is light from light, true God from true God. The eight-pointed rays remind us of the days of creation: the seven days of creation are followed by the eighth, the day of the new creation, the eternal day which is breaking upon us. In this regard, what is fascinating about the Transfiguration is that not only is Christ shining, but his flowing garments shine too. So much more than a merely spiritual event, matter itself is being caught up in the mystery of God and through Christ the whole of the cosmos is being renewed.

The tablets of stone on which the Law was written, held by Moses.

Moses & Elijah. On either side of Christ, there stand the two great figures of the Old Testament: Moses holds in his hands the tablets of stone on which were written the Law, and Elijah, dressed in camel skins, holds a scroll, for he represents the prophets who proclaimed the Word of God. Whilst these two figures are speaking face to face with Christ who is the fulfilment of the Law and the Prophets, the other disciples are unable to behold Christ’s glory. Perhaps we catch a glimpse here of Heaven where we will all be able to see God face to face.

Peter, staring intently at the mystery before him.

The Apostles – Peter, James and John – are on their knees in adoration, screening their faces, and falling backwards before the glory of God. John has even lost his shoe, perhaps in the drama of the moment, perhaps too reminding us of Moses’s encounter with the Lord in the burning bush when he was asked to remove his sandals for he stood on holy ground. All three disciples are in part clothed in blue garments, sharing the life of Christ. The positioning of the disciples beneath Christ and the shape of the curved wall extending out towards us helps us to understand that we too are participants in this event, embraced by the mystery of God’s light.

John, kneeling on the mountaintop, has lost his shoe in the drama of the moment.

The mountain with its solid, craggy top, emphasises that this divine event is taking place on earth. Its ruptured surface gives the impression that the earth is trembling beneath the majestic voice of the Father from on High. The tree to the side points to Christ’s forthcoming passion, about which Jesus, Moses and Elijah are speaking of, reminding us that a share in God’s glory can only come about through a sharing in His cross.

A curlew. Anyone who has roamed on the Moors around Lancashire will be familiar with its haunting call.

The foreground with its gentler hills displays plants and wildlife that are characteristic of the Trough of Bowland, an area of upland bog that flanks the city of Lancaster. There is a curlew with its down-curved bill and haunting call, and a hen harrier, a beautiful, agile bird of prey, renowned for its aerobatic sky dances. There is also Bog Rosemary, a heath shrub, and Cloudberries, a variant of the wild rose. These remind us that the event of the Transfiguration is not something that is limited to first-century Palestine, but an event that continues to become present in our own day as we bend our knee to Christ, who makes himself present in the celebration of Mass, renewing the whole of creation and the whole of history.

Bog Rosemary

The Project.

Lee Richards & Co, our wonderful lime plasterers, who spent two weeks over Christmas building up the layers of lime.

Fran, Martin and Aidan, enjoying a lunchbreak (very healthy looking one too!)

The spectacular icon of the Transfiguration was executed by the internationally-acclaimed artist and iconographer, Aidan Hart, in March 2017. Using a combination of water, egg and pigments made from natural earth and semi-precious minerals (such as azurite), the image before you was built up from basic outlines. Each figure was modelled with layer upon layer of tempera, and over the course of two weeks, it seemed as if the figures were released from the wall, and finally brought to life as they received a sheen of light over the rich colours from which they were made.

This process reflects the way in which God has made us, drawing us from the dust of the earth and breathing into us His Spirit. The transformation of lime, grit, pigment and water into the living image that can be beheld today is itself deeply sacramental, a transfiguration of matter itself.

Drawing from the rich and ancient iconographic tradition exhibited in the ancient monasteries and churches of the East – St Catherine’s Sinai, Constantinople and Thessalonika – the image of the Transfiguration in the Catholic Chapel at Lancaster University presents a significant addition to the Christian patrimony of the North of England. A profound debt of gratitude is owed to Bishop Michael Campbell, the staff, students and friends of the University of Lancaster, the Chaplaincy Centre Management Group, Aidan Hart, his apprentices and those who prepared the groundwork, and the countless benefactors, who have enabled this project to come to its fruition. The artist writes, ‘I pray that, like Christ’s transfigured garments, this inanimate paint might be a bearer of uncreated light to those who stand and pray before the icon’.

Students admiring the work on the night of its completion.

“You can admire a painting by your eyes, but you admire an icon by your soul. When you see this fresco and then go back home, all you can think about is the Transfiguration”

“What a transformation! What a transfiguration! Our’s is an incarnational religion, so the visual aspects of our churches should speak to our senses - this certainly does, raising the heart and mind to God.”

“I love the inclusion of the local fauna and flora which I see on my drive to work through the Forest of Bowland. Let it inspire us (and the many future cohorts of students and staff) to find Christ everyday in our work. Thank you too to the artists for saving us from climbing to the top of the mountain; each day we can come just here to see them!”

“I’m so grateful this happened during my extended visit to Lancaster University. Seeing this artwork grow each week has been a beautiful experience.”

“I am new to faith, but in a moment of darkness I came into this chapel and I locked eyes with Jesus and felt touched by His presence.”

“The fresco is beautiful and filled with a holy presence. Christ’s gaze seems to be an unequivocal invitation to follow Him, to enter into Him, into the eye of eternal life behind him, for He is ‘the Way, the Truth and the Life. Anyone who follows me will have the light of life’.”

“The Fresco is simply AMAZING! Now the chapel looks more alive, and immediately invites to prayer and reflection. Beautiful work.”

In 2018, Pope Francis will invite Bishops and others to Rome to talk about Youth, Faith and Vocational Discernment. At this gathering they will discuss how the Catholic Church can accompany young people in their faith and help them to hear God’s call. If you are aged between 13-29 years old, the Catholic Church in England and Wales would like to hear from you, we want to hear what life is like, your thoughts on faith and how you connect with the Catholic Church. To help you tell us we have created a Youth Poll. For queries about the Youth Poll please email: synod2018@cbcew.org.uk.

Transfers are taped to the wall, to prepare the outlines of the design

After one year and a half of planning and preparations, the world-renowned iconographer, Aidan Hart has arrived at the University of Lancaster to complete one of the largest secco paintings that he has ever done and the first at any academic institution in the UK.

Scrolls of transfers.

Just returning from Houston, where he has been working on a splendid series of mosaics at St George's Basilica, Aidan will be being joined by two of his proteges, and will hopefully complete the work over the next two weeks.

Over the past two days, tower scaffolding has been erected, paints have been assembled and enormous pre-preapred transfers have been stuck to the wall, so that the image in outline could be transferred to the lime-plastered wall. The first brush strokes this evening have released the face of Moses.

The plan!

If you would like to follow progress of the project over the next few weeks, we have a time-lapse camera recording the event. Rarely has an artist been recorded in this way, and the aim is to help a wider public to consider what is involved in putting together great art.

If you would like to be part of this project and to support this project with an donation, you can make a bequest at the Catholic Chaplaincy MyDonate page. You are also invited to an introduction and time of question and answer with Aidan Hart at 2pm on Wednesday 8 March in the Catholic Chapel.

The first outlines of Moses's features.

Over the Christmas holidays, a team of plasterers prepared the wall behind the chapel for the Fresco which is to be painted there at the beginning of March. Much more than slapping on a bit of plaster onto the wall, the whole process has been a complex work of art in itself.

The first stage which was begun just after Christmas was to key the background by hacking into the existing paint and plaster. This then created the suction and grip for the subsequent coats of lime (yes, all 2 tonnes of it!). Betwixt the different levels of lime were adhesive layers and mesh and the lime was mixed with fibres (in the old days they used horse hair) to bind the plaster together.

Finally there was a final skim with crushed marble to give the finish that you see. Over the next couple of weeks the lime plaster will settle and dry out. In this time the colour of the plaster will change and it will begin to radiate a warm luminosity. And then, towards the end of February, the iconographer, Aidan Hart, will be arriving with his team and begin work on the fresco which will take a further ten days. Thank you for your patience as we wait for our chapel to be transfigured!

Hi, my name's Sophie and I'm a recent Primary Education graduate from the University of Cumbria (I did 2 years beforehand at Lancaster University). I'm originally from near Manchester in England but spent the last 5 years in Lancaster where I was a regular at the chaplaincy.

However now I lead a somewhat different life, I'm a Catholic missionary with NET Ministries Ireland. NET is a Catholic youth ministry that encourages young people to love Jesus and embrace the life of the Church. It's a path I never would have thought myself capable of doing back in first year of university, but God is faithful and with Him my life has been so much more fulfilling than I could have ever imagined.

I come from a family who would have called themselves Catholic, I went to Catholic schools, we occasionally went to mass, I received my Sacraments of Initiation but it wasn't until I was in my final years of secondary school that I truly and personally encountered Jesus for the first time. My time at university was great and I had some wonderful experiences, but it was here that I was able to develop a relationship with Jesus. I also experienced the spiritual highs and lows of being a Catholic at university, having to defend Church teaching at 3am in the flat kitchen, trying to explain a new-found love for Jesus to family or finding faith when life seems to be falling apart. However I made some incredible Christian friends who helped keep on the right track and held me accountable to going to mass and keeping prayer as part of my routine.

During my final year at university, I was praying hard about what I was supposed to do after I qualified. I was set to graduate with good grades andreferences so obviously the presumed route would be to get a job in a school, complete my NQT year and start my teaching career. Yet, for some reason this didn't appeal to me. I knew it was what was expected of me, and would allow me to do all the 'grown-up' things like getting a house, a car and the dreaded 'setting down'. I am passionate about education and one day I hope to have a job in a school, but it just wasn't the right time for me to start just yet. I know that when I get busy, and stressed, I forget to pray, I can turn away from Jesus, I wanted to have my heart rooted in Christ before beginning my career. I couldn't ignore the niggling feeling that God was calling me to give a period of my life specifically to Him, to bring Jesus to other young people, to give youth the same opportunities to grow that I had received.

So, months later, after graduation, applications, interviews and training, and plenty of prayer, I'm now settled in to my new mission field and I love it! NET has completely exceeded any expectations I may have had before hand. We have had so many great adventures as a team such as hiking in the mountains, helping lead a Youth 2000 retreat, putting on a praise and worship night and making friends in our community, particularly with the priests and religious. Soon we will be going into schools to give retreats, which includes delivering talks, activities, dramas, music and prayer ministry. Not only are we carrying out ministry but I'm growing in my knowledge of the Catholic faith and Church teaching, and in love for the gift of the Sacraments from the Church. I'm being stretched and challenged in ways I never expected; missionary life is a radical way to live out the call from Pope Francis for youth to be counter-cultural, as a team we strive to call each other on to holiness.

One of the areas I've had to grow in most is surrendering to God, I am learning to give everything to Jesus. A striking moment for me so far was on training during a prayer evening, we were encouraged to write on a piece of paper everything that we wanted to surrender. At first it was difficult to admit to myself how much I love to be in control and how little I allow God to lead my life, so I asked Jesus to show me all of the areas I need to surrender to Him. A few minutes later my paper was full, I had written down my weaknesses, my strengths, my future, my vocation, relationships with my family and friends and my possessions. I then went and nailed this surrender to a cross placed in the middle of the room, my heart beating fast as if Jesus was asking me to give Him my heart too in surrender. I remind myself of this encounter every day, there's nothing in my life that's too big or small for Jesus to handle!

Pope St John Paul II once said to young people "It is Jesus that you seek when you dream of happiness; He is waiting for you when nothing else you find satisfies you; He is the beauty to which you are so attracted; it is He who provoked you with that thirst for fullness that will not let you settle for compromise; it is He who urges you to shed the masks of a false life; it is He who reads in your hearts your most genuine choices, the choices that others try to stifle."

Serving with NET Ministries has shown me the truth of these words, that while I love adventure, only Jesus is going to satisfy the restlessness in my heart. He has called me to this mission and I am so excited to live out the plans that He has in store for me this year, and for the rest of my life!

If you would like to find out more about our ministry or if you would like to join us in our mission to bring the Good News to young people, you can visit my page on the NET website: www.netministries.ie/sophie-benson

Recently we were privileged to welcome Archbishop Sebastien Shaw of Lahore in Pakistan and Sr Annie Demerjian from Aleppo in Syria. The event was organised by Aid to the Church in Need. Both our guests were able to share from their experiences the tragedy of terrorism and conflict.

Archbishop Sebastian spoke of how Pakistan's Blasphemy Laws were being used routinely against Christians and how the growth of fundamentalism was pushing the Church underground. He spoke of his work to generate inter-faith dialogue to develop areas of commonality and his involvement in the political process to stem the misuse of the Blasphemy Laws, and his efforts to explain that the Christians in Pakistan are not a fifth column of an Imperialist West, but of the same soil. The Archbishop spoke with great pride of the contribution of Pakistan's Christian population; though they represent only 3% of the population, the Church witnesses to the Risen Lord through her schools and educational establishments, through healthcare and works of mercy.

Sr Annie spoke of the events in Aleppo, a place we have got to know through the news. But to meet someone who lives there brought the whole tragedy of war to the fore. She spoke of the shrapnel embedded in people's bodies as they go about their everyday tasks, the difficulty of learning how to live without legs and arms, the reality of death everywhere, the sounds of ambulances, shells, missiles, the smell of fear. Families are divided because of death and displacement. In these desperate times the Church is providing the basis of a welfare state, coordinating food distribution, caring for the elderly, helping where she can. Sr Annie even brought with her some pictures that some of the children from her school had drawn of the traumatic events that they had witnessed.

On Wednesday 23 November ACN are sponsoring an event called Red Wednesday to remember all Christians and other faith groups who suffer for their beliefs. ACN is asking schools, universities and groups to stand up against religious persecution and to make a stand for peace and tolerance by wearing an item of red clothing on the day. During our Holy Hour on that day, we will offer prayers for our persecuted brothers and sisters.

A sketch of the design that Aidan Hart will paint.

Behind every great work of art there are patrons. Often in medieval art, you can see the patrons tucked away in the corner of the picture, but included in it. Michaelangelo's great frescos in the Sistine Chapel, Bernini's colonnade in St Peter's Square, all the great churches and cathedrals of the world. They all came together out of the generosity of many benefactors.

Here at Lancaster University we have the possibility of contributing something of significant beauty to the patrimony of the Chaplaincy Centre, the University and the City of Lancaster. Aidan Hart is a world-acclaimed iconographer and will lead a team in the early new year of 2017 to create a vast secco painting, 4m by 10m, of the Transfiguration of Christ, in the Catholic Chapel.

Hundreds of students pass through the Chaplaincy Centre each week for all sorts of different reasons, passing directly by our chapel. We hope to create something beautiful that can be enjoyed by all students, whether they are people of faith or not. 'Beauty opens up and broadens horizons of human awareness', writes Pope Benedict, 'pointing us beyond ourselves, bringing us face to face with the abyss of Infinity, and can become a path towards the transcendent, towards the ultimate mystery, towards God'.

An sketch of what the image would look like.

The story of the Transfiguration is so resonant for a university: Christ is leading his disciples up the mountain, he is transfigured with light, revealing the divine truth of who He is, and He is seen speaking face to face with Moses and Elijah. The story draws together all the mysteries of the Christian faith, uniting Heaven and Earth in the person of Christ, and revealing to us our ultimate end to see God face to face. The hope is that the secco will be painted with such beauty that those who behold the image will be drawn into the experience itself.

A secco of the Transfiguration produced by Aidan Hart in Our Lady of Lourdes church, Leeds.

We are delighted to have commissioned iconographer and painter, Aidan Hart, to do this work. Aidan has studied his field in Britain and Russia and lived on Mt Athos in Greece for three years. Well known overseas as well as in the UK, he has worked in 17 countries and in many cathedrals. We are blessed to have secured his enthusiasm for the project.

Aidan Hart (on left side of picture) in his workshop

Can you help? We are looking to fundraise for this project. We believe that this is a great investment that will benefit all who come to this university chapel for many years, providing a lasting impact upon the students and staff. We invite you to please prayerfully consider making a financial contribution towards the effort. Blessed Paul VI wrote, 'This world in which we live needs beauty in order not to sink into despair. Beauty, like truth, brings joy to the human heart, and is that precious fruit which resits the erosion of time, which unites generations and enables them to be one in admiration'.

Please check out our MyDonate page (search for 'Catholic Chaplaincy at Lancaster University) or support Fr Philip's Half Marathon for the cause on MyDonate Events Page, Catholic Chaplaincy at Lancaster University. Thank you for your generosity.

In August, some of our students joined other young people from the Diocese at the World Youth Day event in Krakow in Poland. There, they were part of a crowd of over two million other young people from every nation of the world, all sharing and celebrating their faith with Pope Francis.

Gathered together for a candle-lit vigil in a field outside Krakow, the Pope exhorted young people not to go into 'early retirement', not to 'throw in the towel even before the game has begun'. 'It saddens me to see young people who walk around glumly as if life had no meaning', young people who are bored with life and who have confused happiness with a sofa, retreating to the comfort of a sofa, hiding behind a computer screen and holding the world at bay. This 'sofa happiness' is 'the most harmful and insidious form of paralysis which can cause the greatest harm to young people'. Pleading with the young people, Pope Francis said that 'we didn't come into the world to vegetate, to take it easy, to make our lives a comfortable sofa to fall asleep on!' He added that it also saddens him to see young people who have gone after 'peddlars of false illusions... who rob you of what is best in life' and who end up in 'nothingness'.

The fulfilment that we all yearn for, Pope Francis said, cannot be bought, and is not a thing or an object, but a person. His name, he declared, is Jesus. He is the only one who 'can give you true passion for life' and inspire us 'not to settle for less, but to give of the very best of ourselves'. And then the Pope exhorted young people to leave a mark, to have the courage to 'trade in the sofa for a pair of hiking boots' and to get out and to 'set out on new and unchartered paths, to blaze trails that open up new horizons', and to follow the 'Lord of Risk' in encountering him 'in the hungry, the thirsty, the naked, the sick, the friend in trouble, the prisoner, the refugee and the migrant, and our neighbours who feel abandoned', 'to build bridges rather than walls'. Using a football analogy, he declared, that the 'times we live in require only active players on the field, and there is no room for those who sit on the bench'.

Asked to share their favourite memories of the whole experience, Polly said she enjoyed 'meeting people from around the world and just talking to them as friends' because we 'knew that we had at least one thing in common, our faith!' She said she enjoyed the mixture of fun too, 'singing Mamma Mia on the coach, praying a few cheeky decades of the rosary, and becoming really close friends with the other pilgrims, and laughing in the rain when we were soaked to the skin'.

Carina added that she had enjoyed being part of the crowd and 'just being able to see millions of people who were around my age, all gathered for the same thing was extremely touching. The people were so friendly and each individual added to the atmosphere. I am glad to say that I have made so many new friends, not only from England but also from around the world. I met people from countries such as Brazil, America, South Korea and Indonesia. Over 100 countries came together in Blonia Park to welcome the Pope and it was amazing to see so many different flags, many of which I didn’t recognise at first like that of Kazakhstan!'

The next WYD will be in Panama in the summer of 2019.

“When I am lifted up, I shall draw all people to myself.”